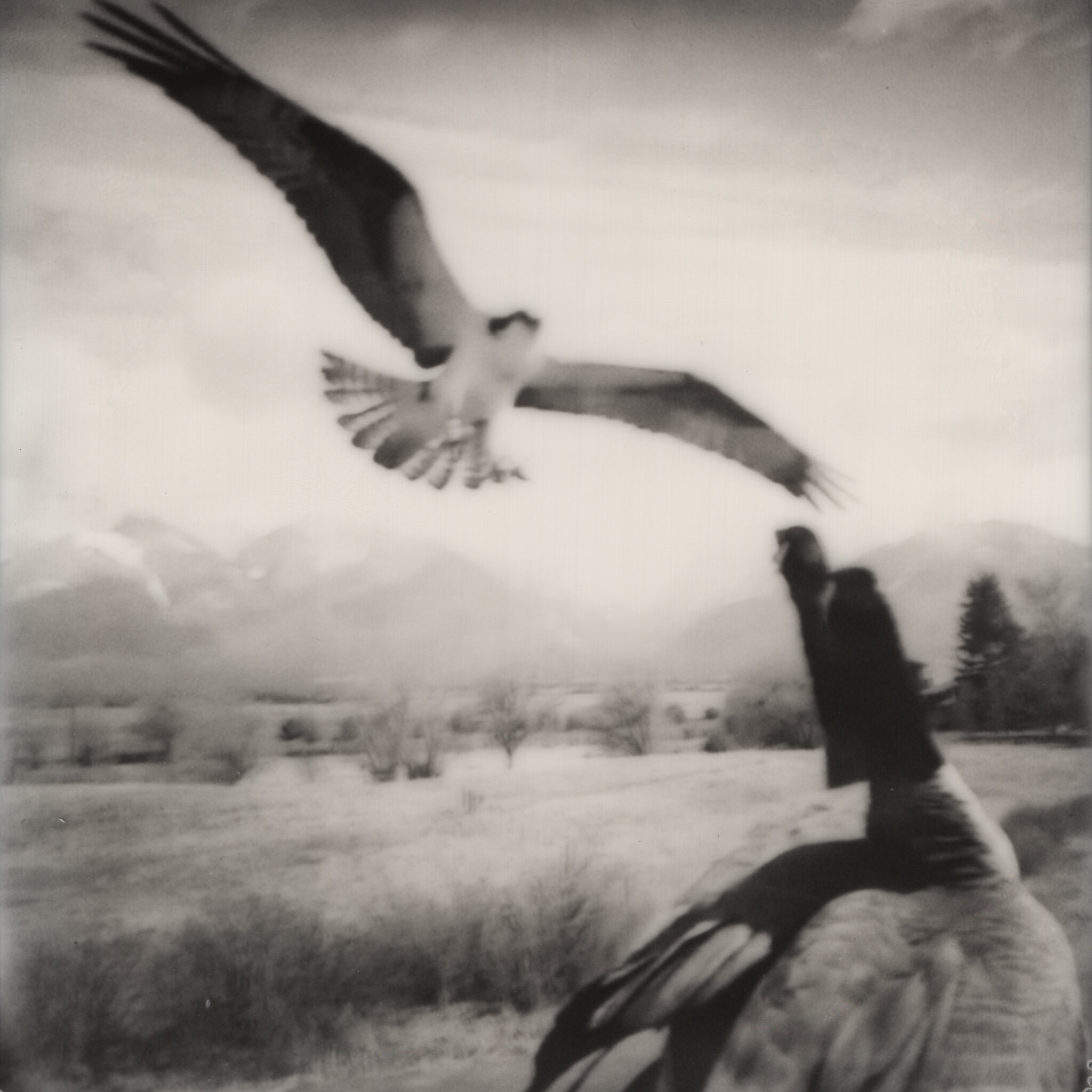

(All the images in the series are instant photographs shot at the screen of my computer while watching live streams of webcams around the world. Only webcams from natural parks, sanctuaries and conservation centers were included - no captive animal or zoo cage has been included.)

The life of a wild animal becomes an ideal, an ideal internalized as a feeling surrounding a repressed desire.

(John Berger, Why Look at Animals, 1977)

Spring 2020.

From my balcony in Torino, I see the Alps covered in snow, the spring sun is starting to be warm, but in the morning the fresh air still smells a bit like winter. The last snow is probably melting slowly by now, filling up the mountain rivers. The grass is already growing under the white cover, flowers will soon blossom coloring the mountain sides.

While most of the world’s population is forced to stay at home because of the coronavirus pandemic, nature is hardly noticing. Seasons change, and while the human population is enduring the worst collective crisis since the end of WWII, animals go about their daily business as usual.

Unable to go out and stuck in my apartment in Torino, I’ve began looking at webcams around the world to escape the boredom and dullness of the homebound routine. But the cities appearing on the screen were empty, the squares deserted.

On the contrary, webcams of natural parks, sanctuaries and conservation centers showed an incredible amount of activity and interaction between species, both gentle and cruel.

The way we look at animals has changed a lot through human history. From god like figures to servants, from respect to over-exploitation and intensive breeding, our relationship with animals has become a purely utilitarian one over the course of the centuries. With the exception of pets, animals are invisible in today’s society. They are machines made for food and - more exceptionally - entertainment. Zoos are one of the few places where we can still “look at animals”, albeit in captivity.

Now, we’re the captives.

In front of a screen, I found myself waiting up until 2am to watch a vulture fly, or a lion kill its prey under the cover of the night.

What kind of pleasure I got from this is a difficult thing to say. Part of it surely has to do with a romantic notion of nature and wild animals, part of it with the fact that, looking at the way animals go about in their daily life, I was somehow experiencing a different concept of time and a different set of priorities from mine.

Many researchers are convinced that the current pandemic is a “clear warning shot” for today’s civilization. Our unbalanced relationship with the planet is to blame for the spillover effect that has caused massive outbreaks in recent years (SARS, MERS and bird flu being some of the past animal borne epidemics). Climate change and the threat to wildlife is another symptom of this sick relationship.

Because of the coronavirus pandemic, we came to a forced stop. We slowed down, in many cases experiencing a different concept of time and a different set of priorities in our own life.

As we plan the future in this brand new world, we need to re-evaluate our relationship the natural world. Looking at animals with the right set of eyes could be a good starting point.